The book, Devil At The Confluence, concerns the incredible stories of over a hundred important musicians from St. Louis who had never been profiled before. Although these musicians were neglected in music history they represent important claims of St. Louis contributions to American culture. And like the recorded blues of St. Louis, the local foods have never really been investigated either. There are the famous local inventions of Iced Tea, Ice Cream, Toasted Ravioli and Gooey Butter Cake, but this essay is an attempt to end speculation with facts concerning the rarely honored St. Paul sandwich. Because just like St. Louis music, other historically important cultural inventions from St Louis have been neglected and ignored for too long.

These new facts about the St. Paul were stumbled upon while researching for the book. It’s bothersome that many St. Louis historical facts and artifacts have been appropriated by other areas and even more bothersome that it seems that the facts were conceded without argument. Some of these claims may seem unimportant such as the creation of Planters Punch or the Tom Collins cocktails, while others are nationally significant cultural traditions such as beer and hotdogs at baseball games. And somewhere in that wide span of cultural importance falls the St. Paul sandwich.

Wiki (and please, kids never, ever confuse Wikis for real research) states that:

“The St. Paul Sandwich is a type of sandwich found in Chinese restaurants in St. Louis. The sandwich consists of an egg foo young patty served with lettuce, pickle slices, mayonnaise and tomatoes between two slices of soft commercial white bread, such as Wonder Bread.”

But Wiki is not the place to look for missing answers to unsolved mysteries. The crowd-sourced and unverified soft-database says:

“The origin of the sandwich is unclear”

followed by this Wiki-wishy-washiness:

“It was invented in St. Louis, Missouri and is usually only available in Chinese restaurants in the St. Louis metropolitan area.”

The St. Louis St. Paul sandwich was featured in a 2002 PBS documentary called “Sandwiches That You Will Like” but the question of the history of the item was answered with a shrug. In the companion book of the documentary, “American Sandwich: Great Eats From All 50 States.” it says that sources (unnamed) claim that the sandwich dates as far back as the 1960s and another source (unnamed) says the early 1940s.

So no one knows the history about the sandwich, yet the sandwich can only be found in St. Louis? Well that’s enough to claim it as a local invention. Really, if this was Chicago that would be enough and it would be up to somebody else to try and prove that it wasn’t. In fact, that’s the way it is for nearly every historical claim to American foods like hot dogs, pizza or pretzels. There just isn’t a lot of documentation on this kinda stuff, so being the only place that has it means it comes from there. This shouldn’t be a mystery.

Or could it be that St. Louis doesn’t want to claim it? Like the gooey butter and fried brains crowd draws a line in the saturated fat and refuses the St. Paul? Or maybe it’s like St. Louis’ unclaimed rights to American music history, a victim of that local inferiority-complex thing - a belief that new or important creativity must have come from somewhere else.

Or maybe it’s not as bad as all that. In the last few years there seems to be a change for the better in St. Louis. There is a new local pride. And the St. Paul sandwich has benefited from it.

In 2009, after Playboy magazine listed the St. Paul Sandwich as one of its top ten sandwiches, but noted that the sandwich might not have St. Louis roots, Joe Bonwich defended the city’s claim in his comments in STLToday:

“This is a one-source legend dating to a 2006 article by Malcom Gay in the RFT, in which Park Chop Suey's owner claims that a former owner of the restaurant, who was from St. Paul, Minn., invented the thing. But there's no corroborating evidence, and the way it's worded, it sounds like the sandwich was invented in St. Paul and migrated here.”

Thank you, Mr Bonwich!

Alone, the sandwich may not be as big of a tourism draw as perhaps the Cheesesteak is for Philly, but maybe it can be. Lunch Encounter, a blog by Washington, DC-based food writer Lisa Cherkasky apparently thinks so:

“Just one more compelling reason to get your sandwich eating self to St Louis, the St Paul Sandwich.”

Thank you Lisa, bring them in. And then she muses about the source of the dish by showing some impressive knowledge of local history:

“I wonder, does it have anything to do with Chinese railroad workers? I would say, after doing a tiny bit of research, yes. In 2007 there were 700 Chinese restaurants in St Louis. That would point, one would reason, to a long history of Chinese-American culture. When you sit in Busch Stadium watching St. Louis Cardinals games, you may never imagine this location was once China Town. The first wave of Chinese came to St. Louis in 1869 when many of them lost their jobs as railroad construction workers. At the peak period, the Mid-Pacific Railroad Company hired over 10,000 Chinese laborers. When the westward railroad construction was completed, many became unemployed. Many of them chose to come to St. Louis that was then the 4th largest city in the United States.”

St Louis' Chinatown was without firm and clear borders just like the many other immigrant areas of the city. The area of Busch Stadium at that same time was also known as Tamaletown, with a large number of Mexican immigrants. In Devil At The Confluence there is an early picture of the headquarters of African-American music, the Deluxe Music Shop and visible next door to it is Wo Hop Chop Suey. Different nationalities and races mixed block-by-block in the city at the turn of the century. And that fact about the confluence city is perhaps most significant to the cultural invention of the St Paul sandwich as noted by none other than frontman for the local alt-country/roots rock band, the Bottle Rockets, Brian Henneman.

“I wouldn't be one bit surprised to find out the St. Paul sandwich originated from the cross pollination of African American culture, and the plethora of local Chinese restaurants.”

And there it is. There is the significant uniqueness of St Louis' cultural history - the merging of styles in a location suited for the creative blending. A common ground that isn't north or south, or east or west, or country or urban. There's a strand of the unifiying thread found across the cultural and creative aspects of the city of the confluence.

So here we add the evidence found during our research. The first image is a photograph from sometime around the turn of the century. Two men stand in front of a typical restaurant on a street in St. Louis, on the wall is posted the menu.

The second image shows the wall menu in the photograph enlarged and enhanced. The second item in the SANDWICHES column on the left reads: “Try our ST. PAUL”

The next images are St. Louis Post-Dispatch newspaper articles. From 1922, the Man On The Sandbox editorial column reads: “Our idea of a civic short order lunch is a St. Paul sandwich on Milwaukee rye.”

From 1918, the Sport Salad column makes reference to a St. Paul sandwich, “which is composed principally of ham and eggs.”

Both of these St. Louis editorials are making esoteric comments on matters of the day that are not known so it’s hard to understand what exactly these comments mean, but they are surely joking about something.

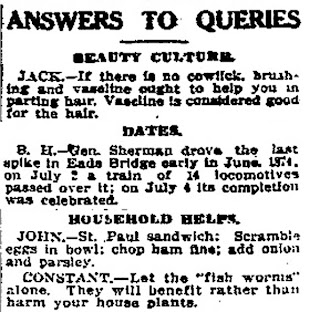

And from a 1916 column replying with answers to unprinted reader’s questions, “John” is told the ingredients for a “St. Paul sandwich: Scramble eggs in a bowl; chop ham fine; add onion and parsley.”

It was at the 1904 Worlds Fair in St. Louis that so many exhibitions tried very hard to show off new inventions and recipes and at least four versions of the Club Sandwich appeared there. This might have been the debut of the American sandwich formula of “meat + Mayonnaise + lettuce + tomato.”

So the history of the St. Paul sandwich has been an established St. Louis restaurant item now for at least one hundred years. It seems very likely that the various Asian, African and European immigrants in the densely populated city was the unique combination of factors that contributed to the creation of the Americanized Egg Foo Yung sandwich with the Catholic name - the Saint Louis Saint Paul.